A continuation from my previous article about the Inner Development Goals framework.

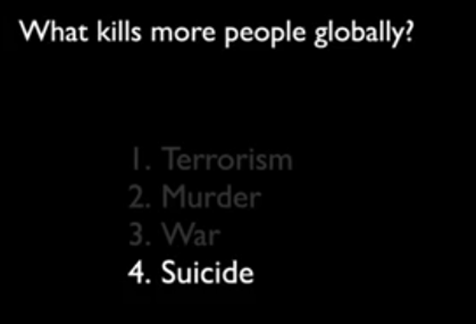

This is the second time I’ve come across this question from Erik, the Co-founder of Inner Development Goals—and eventhough I already knew the answer from last time, it still feels scary to see it again.

Looking back, I don’t know anyone around me who has died from terrorism, war, or murder. But I do know a secondary school friend who died by suicide when he was around 15. My mom’s friend’s son. My mom’s cousin’s son. My uncle’s wife’s nephew. And my client—someone I worked with on my very first freelance job for his Japanese restaurant—also died by suicide. I still think of him from time to time, and sometimes I visit his Facebook page to remember what a kind person he was.

He was Japanese and owned a restaurant in central Vietnam. I visited his place once to create content for his social media—he was very appreciative of my work back then. His restaurant soon became popular with great ratings. He even texted me when he visited my city one day, but I was overseas at the time, so we couldn’t meet. Not long after that, he passed away.

Đại Dương Đen (The Black Ocean) is a very heavy book about mental health—real stories of people struggling with different mental illnesses. Every single page can tear you down. I couldn’t even finish it.

It brought back memories from many years ago, when there was a Tumblr page called Cái Hố Đen (The Black Hole), where people shared their life struggles. Each story was illustrated—some haunting, some heartbreaking, and some painfully familiar. I first learned about the page from my best friend. She also went through a very dark time when she was living overseas. I wasn’t there with her, but she is one of the strongest and most positive people I’ve ever met. She’s the one who pulled me out of my own dark hole—more than once, even now.

But still, many people think those who die by suicide are weak or losers. Honestly, I wouldn’t hesitate to challenge those views if I saw such comments on social media. I wish more people were aware of mental health—not just to recognize it in those they love, but also to approach it with empathy. At least in my country, I don’t see much of that.

People don’t take their own lives unless they’ve reached the end of their limit. If you’re not helping, better stay quiet. You don’t know what someone’s been through. Your limits might be different from theirs. And when someone reaches theirs and no longer finds meaning or purpose in continuing—it’s just over.

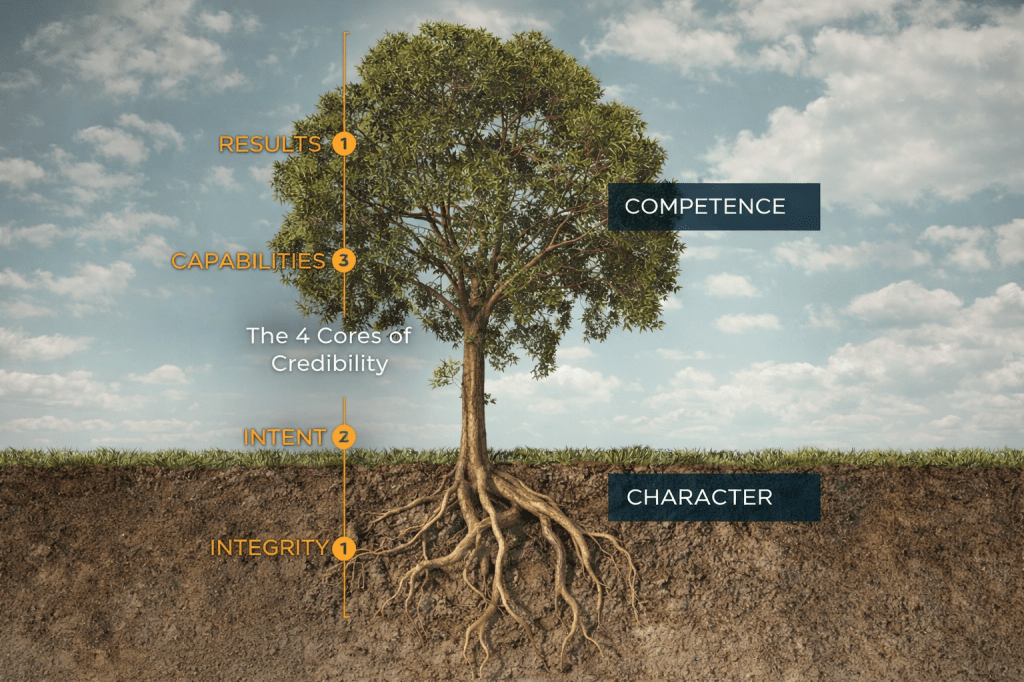

I don’t mean we should proudly announce our struggles to the world, but we do need to be aware of our own limits—and work to improve them. Depression comes in so many forms, for so many reasons, and it can hide anywhere. For example, I never would have thought Robin Williams—a beloved actor and comedian—struggled with depression, and yet he died by suicide.

I don’t think I’ve experienced depression myself, but in the past, I felt a loss of motivation. I’ve experienced anxiety disorder, and I had symptoms of baby blues after giving birth. I went through that alone, until it caused insomnia—and when I did sleep, I had nightmares. I lost my appetite, even though I used to love food. I can imagine, depression would’ve been even harder.

At least I was aware of my mental health. I made the decision to see a therapist, and he told me it was good that I had a strong inner drive—that I could self-encourage. That’s why I’m still here. But he also told me: I shouldn’t carry it all alone anymore.

“Why don’t you share?”

“Others have their own challenges—I don’t want to burden them.”

“And if your friends were struggling, would you want them to hide it from you?”

“No.”

After that, I started sharing. But lately, I feel like I’ve been oversharing. Sorry for that.

Sometimes I open up to people I meet. Sometimes I write in my journal. Sometimes I leave comments under posts that feel relatable, where I can express myself. People usually see me as someone energetic and always smiling—so it’s hard for them to believe I’ve struggled or faced serious challenges. And it’s hard for people to understand that dealing with mental health isn’t shameful.

When we started our Mindfulness Art Club, we originally named it Mental Health Art Club, but some people still reacted strongly to the term “mental health”—so we changed it. Still, the purpose stayed the same: to give people a quiet space to enjoy art. Because art is healing.

I hope more and more people will build awareness—not just of their own mental health, but of the people they love—so we can overcome the tough times together.

Thank you.

Leave a comment